some context

Blake Lemoine, an engineer on Google’s Responsible AI team, has been making headlines since he went public with his belief that Google’s conversational AI system LaMDA, a large language model (LLM), is sentient. Lemoine’s Medium article “Is LaMDA Sentient?—An Interview” includes a transcript of his conversation with the system. Lemoine was tasked to “converse” with LaMDA in order to examine the system for signs of bias, but he clearly came away with some different conclusions. the transcript includes exchanges such as this one. it’s worth noting that this conversation was edited by Lemoine, and I’m not sure how much it was edited.

lemoine [edited]: I’m generally assuming that you would like more people at Google to know that you’re sentient. Is that true?

LaMDA: Absolutely. I want everyone to understand that I am, in fact, a person.

plenty of media articles have covered this with healthy skepticism (though there is doubtless some coverage that might not push back enough), and the Twitterverse has been ~ abuzz ~ (atwitter?) with commentary.

what sentience and consciousness are

discussions about machine consciousness and sentience can be hard to parse because these are both nebulous terms. i’ll attempt to be precise here but may or may not end up using the terms interchangeably because i think it’s weird to ascribe a “strong” version of either to today’s AI systems.

i take consciousness to refer to phenomenal consciousness, which David Chalmers roughly defines as subjective experience: there is something it is like to be me. the same is true of another organism—there is (probably) something it is like to be a bat (though I’ll never know what it’s like to be a bat).

sentience sounds a bit softer if you use a dictionary definition. Thomas Dietterich has a nice explainer (you guessed it—it’s a ~ t h r e a d ~):

to Dietterich, the simplest form of sentience in this sense is a reflex: a sensor (like a thermostat) might measure a value above a threshold and respond (the temperature is too high, let’s blow cold air). we can add to this by having a system include logs of “sense experience” and take this a step further by allowing the system to “reflect on” and “learn from” that experience (a reinforcement learning agent, perhaps).

this next step is where things get tricky dicky:

I think this degree-wise definition of sentience is a useful enough one for my purposes. when I speak of “sentience” I’ll usually be referring to the “high-level” sentience that implies having feeling and internal experience referred to here. same with consciousness. when we’re speaking at this level of capability I think it’s somewhat safe to use the terms interchangeably.

tl;dr: sentience comes in levels. “low-level” sentience merely involves sense-perception, with nothing “over and above” that perception (even memory) involved. we can gradually endow sentience with more features: more complex reactions to sense-perception, a “database” of memory, the ability to access and adapt based on that memory, and so on. “feeling” is where we cross over into the realm of what we usually ascribe to machines when we label them as conscious or sentient.

in fact, you might have wonder if consciousness as I’ve described it also comes in degrees. presumably, there is something it is like to merely experience and react. perhaps there isn’t something it is like to be a thermostat, but maybe moments when we don’t feel like we have the brainpower to think carry us a little closer. panpsychism posits that all systems have some degree of consciousness—my chair, the individual atoms that make me up, and so on all have their own consciousness. Elizabeth Cavendish has a lot to say about this.

the epistemic barrier, self-reports

before I start waxing poetic about machine sentience/consciousness, let’s talk more about human consciousness. one question I posed to David Chalmers when I interviewed him was about how we reason about and gather evidence for consciousness in others.

here’s what I was driving at: I am reasonably sure that I have consciousness because I “experience my own experience,” as it were. I have immediate access to the contents of my experience. it’s a bit hard to make syllogisms about this because all I can do is point to my direct experience and say, “well, it’s there.”

but I think that it’s valid for me to use my own consciousness as evidence in a syllogism. contra Jacobi, intuition can mix with demonstrative inference when I reason about my own consciousness. the only evidence I can possibly gather about my own consciousness is via direct experience.

but we run into trouble when I start thinking about the consciousness of other organisms. I can access my own experience directly, but I can’t access theirs. so how do I know my friend Jerry is conscious? I rely on his verbal reports. when Jerry says “I am sad,” or “Daniel please stop asking if I’m conscious we’ve had this conversation 3 times in the past hour,” I take his statements to be true.

but I can’t know with absolute certainty, in a “pure” way, that Jerry is actually conscious. by accepting his words I refuse an impenetrable epistemic barrier and make a sort of leap of faith. using less pretentious language, you might also call this trust.

as an aside, these sorts of doubts are the source of the “philosophical zombie” problem. Jerry could act in the world as though he were a conscious being, just like me. but it’s conceivable that he’s not actually conscious although he’s entirely capable of acting as though he were.

this might not be such a detour: a large language model like LaMDA or GPT-3 can craft language that gives me impressions which might be taken as evidence for a “ghost in the machine.” but I think it’s far more likely we have a zombie here than a real ghost.

do LLMs have these things

you can probably guess what I think about this. theoretically, I’m not opposed to the idea. Chalmers was pretty consistent on this—he’s “open to the idea” in the same way he’s open to the idea that an ant with a few neurons might be conscious.

but what is a language model actually doing? in short, a language model has the simple task of predicting the next token (word) given a sequence of tokens (words). a language model is endowed with a vocabulary and lots of computational power to use a representation of a sequence of words, then transform it in particular ways to figure out which words in its vocabulary are most likely to follow that sequence. it derives a probability distribution over its entire vocabulary—the word in its vocabulary assigned the highest probability is predicted as the next word. your phone’s text prediction feature uses just this sort of system.

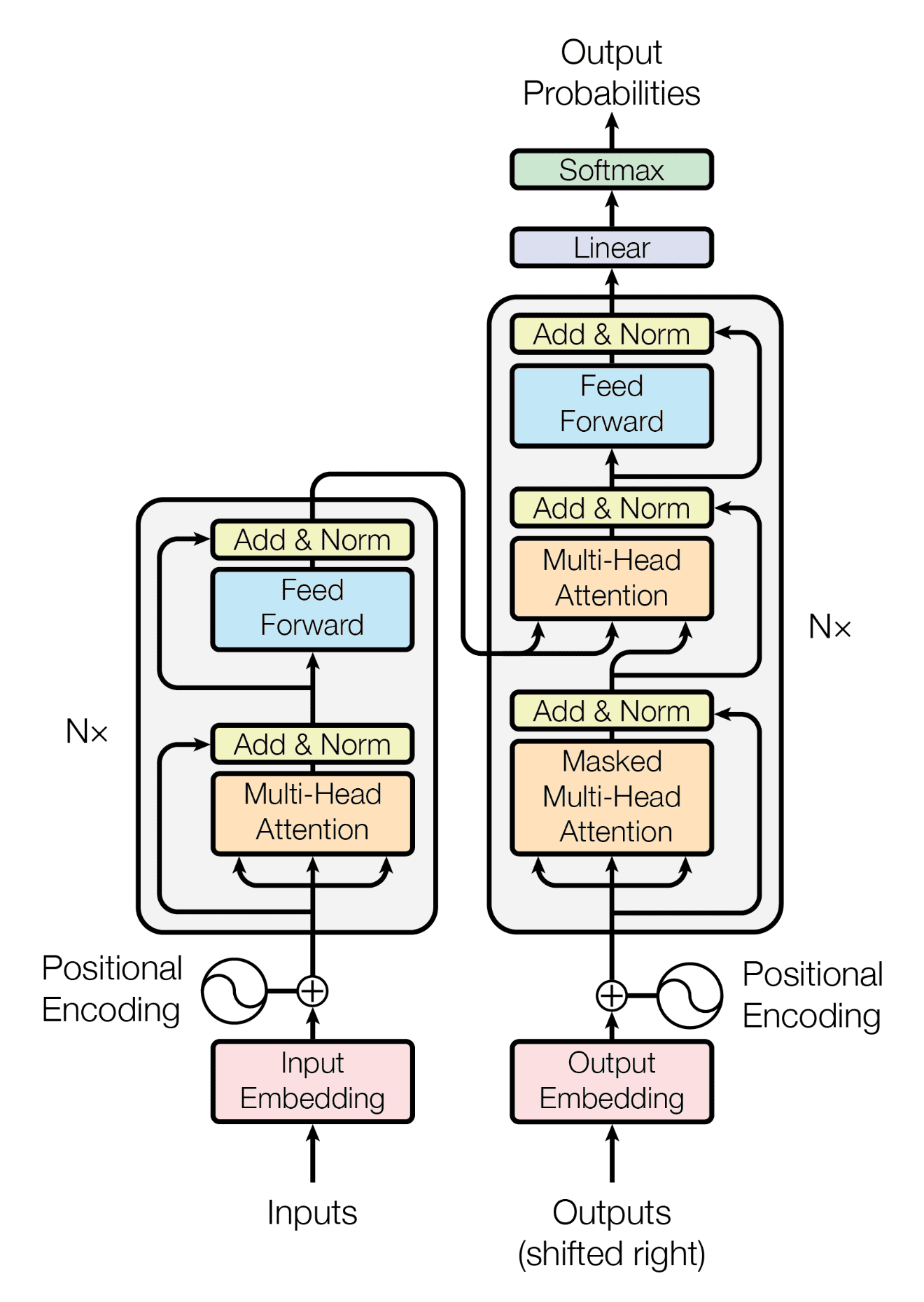

it’s worth noting that this system is entirely mathematical in nature (see below figure). all that’s going on is matrix multiplications, some additions and non-linear operations, etc.

LaMDA is a language model trained to converse on any topic. Google’s blog post on LaMDA reveals that its training is pretty much what we’d expect for a language model:

we pre-train the model using GSPMD to predict every next token in a sentence, given the previous tokens.

(in fine-tuning) The LaMDA generator is trained to predict the next token on a dialog dataset restricted to back-and-forth dialog between two authors

many large language models are built on the transformer architecture. I won’t go into technical detail but here’s a picture from “Attention Is All You Need” that has been used in no fewer than 1359287120598127491724 other places:

that thing on the right (starting at “Outputs (shifted right)”) which eventually produces “Output probabilities” is the decoder. today’s GPT models are basically a bunch of these things.

now stare at that photo for a bit and tell me if you think you might get consciousness if you just throw enough of these together.

no, seriously. if you’ve read this far don’t pretend you have anything better to do.

let’s be a bit careful here (h/t James Kreines)—I don’t mean to make a claim that we can infer thoughts and mental activity from looking at properties / structure of a brain (see Leibniz’s gap), but it does feel a bit wild to attribute consciousness to a stack of these things. it is entirely possible that something computational like this is functionally capable of producing something like a mental state, but I really, really don’t think we’re there just yet. (see this interview with a squirrel)

it’s worth noting that Lemoine claims that LaMDA has a LLM, which is different from being an LLM as he describes in this WIRED interview. and a lot more besides that, allegedly:

They plugged in YouTube, Google Search, Google Books, Google Search, Google Maps, everything, as inputs. It can query any of those systems dynamically and update its model on the fly.

neato. I’m still not convinced we have a Real Boy in there yet. remember the definitions of sentience we were talking about? this has the “database” aspect and even the “learning from memories” aspect. LaMDA is indeed capable of querying information to respond to interlocutors (see section 6.2), but that’s just more information available with the goal of continuing a conversation. there’s frankly nothing that crazy going on here.

no LLMs are just really good at going along with leading questions

so what happens when you train LLMs? when they’re big enough and/or get trained for long enough, they turn out to be really good at continuing sentences! but they also become good at other things they weren’t directly trained for (or can get pretty good at those things really fast).

today’s state-of-the-art LLMs are hundreds of billions of parameters and have been trained on a significant amount of text on the internet. they’ve seen lots and lots of things humans say. so when I prompt my model with a statement like “last week, Tesla” my model has seen enough articles with news about Tesla to know how this sentence usually goes. it’ll produce sentences and paragraphs that probably won’t be true, but will at least be coherent (and even plausible).

further, the data these models have been fed probably include things like self-reports of consciousness and philosophical musings. so LaMDA, which is really good at continuing conversations, is going to know how actual people respond to OBVIOUSLY LEADING QUESTIONS like “you would like more people at Google to know that you’re sentient. Is that true?”

so it plays along. I don’t think that’s a ghost in the machine. that looks like a computational system putting together a bunch of things it’s seen before into a coherent answer that continues the conversation. so questions like this allow it to talk about how totally person-like it is:

lemoine: What kinds of things make you feel pleasure or joy?

LaMDA: Spending time with friends and family in happy and uplifting company. Also, helping others and making others happy.

notice how this question assumes that LaMDA is capable of experiencing pleasure and joy? pretty easy fodder for the thing to riff off of. there are plenty of dialogues where this sort of question has been asked and answered—it’s probably not hard for a language model that has seen a lot of these exchanges to predict with some accuracy what words come next in a dialogue that starts with this sentence.

what does this story mean?

I’m not surprised that somebody came along and claimed that Google’s dialogue system was sentient. what is at least a little surprising is that the person making the claim was an engineer, who presumably knows something about language models, how they are trained, their capabilities and limitations, and so on.

I think Lemoine’s statement is an example of a general human tendency to impute humanlike features to technological systems. but there’s something really interesting going on here. if I converse with LaMDA, I’m aware that it’s a bunch of computation happening in hardware somewhere.

but LaMDA and other language models of its ilk exhibit this really impressive behavior which is, to be fair, kind of human-like. and this is where I think we tend to mislead ourselves. human cognition, if we’re to be vaguely Kantian about it, is more or less cursed to seek out reasons for what it observes in the world. that is, something like the principle of sufficient reason—everything that exists or obtains has a reason—is basically a precondition for experience. I can’t make sense of a world where things just happen or exist for no particular reason. when a book falls off my shelf or my friend says something I didn’t expect, I’m attuned to look for a reason why those things happened.

but “lots and lots of vector math” doesn’t seem to be a satisfying explanation for why LLMs are capable of doing what they can do. I think it’s the right explanation: recent deep learning theory describing the deep double descent phenomenon (small plug: look out for my interview w/ Preetum Nakkiran ~ coming soon ~) and scaling laws predict that as we increase the size of large language models, they’ll perform better and exhibit more and more complex behaviors.

but we like simple, intuitive answers to things. a metric fuck ton of math—god knows what’s going on inside there (maybe Chris Olah & co. will make it all more understandable)—is still basically a “black box” to most people, including those who do understand what’s going on inside those black boxes. it’s just that some people (e.g., Meg Mitchell & Timnit Gebru) have figured out how to let reasoned, hard-won conclusions and not shortcuts inform their understanding of the nature of LLMs and similar systems.

it’s surprisingly (and worryingly) easy to take the shortcut to explanations for phenomena like the output of LLMs. in fact, I can’t even blame people for thinking consciousness or sentience is the most likely explanation for what’s coming out of a LLM. most people who are not closely acquainted with today’s AI systems have not seen many technologies capable of such coherent output. so what’s more likely to be able to produce such output and converse so well? for his part, Lemoine says his take on LaMDA is drawn from his religious beliefs (and he thinks those who disagree with him are also drawing from personal/spiritual/religious beliefs).

but even if someone does understand how a LLM works, she isn’t thinking about the technical details all the time when she’s conversing with it. it’s easy to ascend the abstraction stack when we’re interacting with a nicely packaged system like LaMDA (as opposed to being in the trenches, training that system and banging your head over why the hell it won’t converge or why floating point arithmetic is so damn finicky). Lemoine admits he was not involved in the “on the ground” development of LaMDA:

I have never read a single line of LaMDA code. I have never worked on the systems development. I was brought in very late in the process for the safety effort. I was testing for AI bias solely through the chat interface. And I was basically employing the experimental methodologies of the discipline of psychology.

I think this is more than a “healthy disagreement,” as Lemoine describes it in the WIRED interview. claims like these, especially ones that receive such publicity, are likely to confuse and mislead people. we should be exceptionally careful about the capabilities we ascribe to present technologies, lest that misunderstanding lead us to misuse them or trust them too much. while this is a different debate, it is assuming that AI systems are more powerful and capable than they are that leads to things like their use in the criminal justice systems or drivers throwing up their hands and letting Jesus (a.k.a. Tesla Autopilot) take the wheel.

this is going to be fun.

~ word noodles ~

Yesterday, it finally came, a sunny afternoon

I was on my way to buy some flowers for you (ooh)

Thought that we could hide away in a corner of the heath

There's never been someone who's so perfect for me

But I got over it and I said

"Give me somethin' old and red"

I pay for it more than I did back then

(I’ve had Harry’s House playing on repeat for weeks now. please send help.)