This puzzle [of engaging with Chinese] would have to be solved quickly, though, for it constituted nothing short of a civilizational trial by which to judge once and for all whether Chinese script was compatible with Modernity with a capital M (The Chinese Typewriter, 10).

How does a civilization process its relationship with modernity?

I studied Chinese in high school and college, and in an intro class, what immediately confronts you is the interface between writing and meaning. You learn that 人 means “person” and can kind of see how that works. You start to see 人 (rén) as a radical in other characters: 他,休,你. You also notice that it looks different as a radical as opposed to a standalone character.

When you approach a keyboard and want to write Chinese, what do you do? If you’re learning Chinese at an American high school, this might seem natural enough: you write the pinyin. But if you switch your keyboard language from English to Chinese, so that you can type the actual characters, you’ll discover a few things: if you want the characters for ‘jíshǐ’ (even if), type ‘jishi’ and you’ll see a pop-up menu with 即使 as the first option—you can then type ‘1’ to confirm your choice. Type 2 and you’ll get another pair of characters.

But you can also generate 即使 by other means: type ‘js’ on your keyboard, and, at least in my case, the first option on the pop-up menu is 就是. But, if you’re willing to expand the pop-up menu and scroll far enough, you’ll find what you were looking for. The next time you type ‘js’, 即使 might appear closer to the first pop-up menu option than it did before.

But this solution to typing Chinese, probably obvious to a non-native speaker, can’t have been the full story. Hanyu pinyin was only invented in the 1950s, and the global advent of telegraphy occurred more than a century earlier. Methods of communication and inscription—importantly, typewriters—existed before we possessed a standard method for transcribing Chinese characters into the Latin alphabet.

So, how did we get here? As it turns out, there’s a fascinating history behind the technologies that afford our ability to type letters into a keyboard and see characters on our screens—and it extends far beyond our computers.

One of the tools we were often exposed to in philosophy—sometimes used in proofs or arguments—was that of a contradiction in terms. A square circle (or a circular square) is a contradiction in terms; by the definitions of the terms that compose it, such an object can’t exist.

A contradiction in terms can tell you a lot. Maybe one of the terms you used does not mean what you think it means. Maybe the procedure you used to arrive at the contradiction in terms is incorrect. In the Transcendental Dialectic, Kant used four antimonies to illustrate a fundamental issue with our ability to cognize transcendent reality with pure reason: for instance, with the same set of assumptions, you can prove both that an absolutely necessary being exists either in the world or as a cause of the world, and that no such absolutely necessary being could exist.

With this in mind, consider the object denoted by “Chinese typewriter.” Can you imagine it? What does it look like?

Chinese characters don’t look like what I’m typing now—unless we use pinyin, they don’t admit of Latinization. So let’s look at the other term: what’s a typewriter? Let’s ignore the fact that people were also called typewriters for now, and consider the mechanical machine. Wikipedia offers this:

a typewriter has an array of keys, and each one causes a different single character to be produced on paper by striking an inked ribbon selectively against the paper with a type element.

This sounds uncontroversial. So, with this in mind, return to “Chinese typewriter.” If a typewriter key causes a single character to be produced on paper (let’s, for now, abstract away the physical implementation of this process), can the typewriter accommodate a language like Chinese?

Probably not. The HSK (汉语水平考试 Hànyǔ Shuǐpíng Kǎoshì: Chinese Proficiency Test) is used to assess non-native speakers, such as foreign students wishing to study at a Chinese university. If you want to take classes taught in Chinese at Peking University, for instance, you’d need a certificate for HSK 6, the highest level—this tests your knowledge of 5,000 characters.

5,000 characters. For a moment, let’s use HSK 6 proficiency as a proxy for literacy / proficiency in Chinese. Now return, once again, to “Chinese typewriter,” and bear with me as we do a quick calculation: if you need to know 5,000 characters to be proficient, and you want to type those characters, and a single typewriter key impresses a single character on paper, how many keys do you need to type all the characters a proficient Chinese speaker should know?

Can you imagine sitting in place, composing essays, on a typewriter with 5,000 keys? This sounds hard. If the typewriter is a static object, one key to one character, can you write the contents of an HSK test with it?

Contradiction in terms. Square circle.

Let’s take the argument a step further. Typewriters and their ilk, for much of the literate world, were harbingers of modernity. The typewriter changed the shape of the business world, increasing efficiency in work and correspondence. Waller, who writes of the typewriters impact on womens’ employment and its effects on the economy and culture, concludes that it is an invention of serious magnitude—on par with the telephone and electric light.

So, the typewriter changes the world, ushers it into modernity.

The Chinese typewriter does not exist.

The Chinese typewriter cannot exist.

Who gets to participate in modernity?

I’d read at least an essay by Lu Xun in one of my Chinese classes, but I never knew that he was a character abolitionist. Professor Thomas Mullaney wrote (emphasis below is my own):

The celebrated writer Lu Xun (1881-1936) was yet another member of this anti-character chorus. “Chinese characters,” he argued, “constitute a tubercle on the body of China’s poor and laboring masses, inside of which the bacteria collect. If one does not clear them out, then one will die. If Chinese characters are not exterminated, there can be no doubt that China will perish.” For these reformers, abolishing characters would constitute a foundational act of Chinese modernity, unmooring China from its immense and anchoring past (The Chinese Typewriter, 13).

Again, we return to the contradiction in terms. The typewriter and its affordances usher in progress. Chinese characters cannot be accommodated by the typewriter. It is characters themselves—which maintain China’s connection with its past—that prevent China from participating in the future and isolate it from a Hegelian sense of historical progress.

There is an interesting point—in McLuhan or in Nietzsche (by way of Nahemas) or in both—that we make a fundamental error in our understanding in the world, in processing our immediate experience, and the universalisms imposed by the alphabet are to blame. I quoted this from McLuhan before:

In Western literate society it is still plausible and acceptable to say that something “follows” from something, as if there were some cause at work that makes such a sequence… Neither Hume nor Kant… detected the hidden cause of our Western bias toward sequence as “logic” in the all-pervasive technology of the alphabet. (Understanding Media, 85).

Mullaney, in his introduction to The Chinese Typewriter, tells the story of an encounter between Chinese script and the International Olympic Committee in 2008, and its uncovering of false alphabetic universalisms. The upshot of all this was that many technologies—ASCII, optical character recognition, digital typography, typewriters—were developed first with the Latin alphabet in mind, then extended to non-Latin alphabets. Maybe, too, they got to nonalphabetic Chinese.

But what to make of these false universalisms, that the logics underlying the Latin alphabet are true everywhere? What to call this history? Mullaney argues that “linguistic imperialism” doesn’t quite fit the bill, and that “Western imperialism” and “Eurocentrism” do not work, either. The hegemony that Mullaney sees is not about West versus East, Europe versus Asia, but rather an all-versus-one divide: one that pits all alphabets and syllabaries against character-based Chinese writing, the one major world script that does not conform.

And, in the history of the typewriter’s development, it was the recalcitrant Chinese script that was to blame for its incompatibility with modern technology. Mullaney writes beautifully about the “technolinguistic Chinese exclusion act”:

the single-keyboard typewriter form would finally relaize its universality by excommunicating from this universe one of the world’s oldest and most widely used writing systems. In the Kristevan sense, the Chinese script was marked as the “abject form”: an object or condition existentially intolerable to a system or state of affairs, and as such one that had to be banished from ontology itself” (The Chinese Typewriter, 65).

Banished from ontology itself.

I find typing pinyin on a keyboard slower than typing English, because I have to figure out the right keystrokes to add tones to the vowels. It’s good to pay attention to tones, because if you say a word with the wrong tones or with no tones at all, you might say something you didn’t mean to say, or sound kind of dumb.

If you say 我 without the third tone, you get something that sounds like “woah.” MC would make fun of anyone who did this in class, drawing out a long “woahhhhhh” in his scruffy baritone.

As it turns out, typing Chinese characters slowly is a skill issue. If you want to, you can type them really, really fast. It took me a little while, when I first learned, to realize I could condense my keyboard entries from full pinyin to just the first letters in the pinyin of each character, but you can summon characters in even more creative ways than that.

Apparently, Hegel used a sort of Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis to argue for the incompatibility of Chinese writing and modern thought—the very structure of Chinese grammar, in his telling, rendered modern thought impossible for its speakers (The Chinese Typewriter, 66).

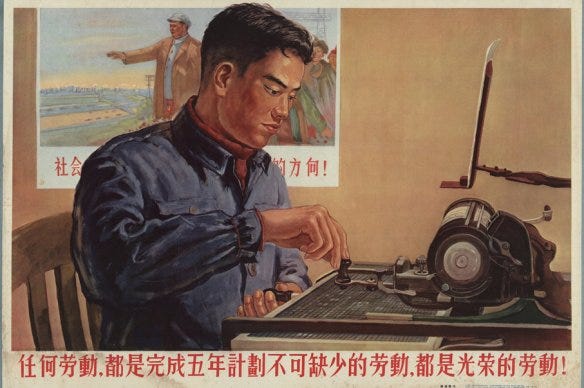

If I search the Wikipedia page for “Typewriter” that I linked above, much of the history on the page comes from Western efforts to create the technology we think of today. Search for the word “Chinese” on the page, and you’ll find it comes up five times (as of this writing). If you follow the mention of “Chinese typewriter” in the references, you’ll find this article about something “almost as complex” as the computer. You’ll find a few images, like this:

What is this? Is it a typewriter?

The typewriter is not a fixed element of reality, a fundamental object in our ontology. Humans created the typewriter. What it is to be a typewriter, then, is tied up with the history of human affairs.

We ran headfirst into a few contradictions in terms above—the collision between “Chinese” and “typewriter.” If we look again at the term “typewriter,” what does it disclose? Mullaney diagnoses our confusion about the Chinese typewriter, our presumption that it is an impossible object, as the result of a conceptual algorithm (The Chinese Typewriter, 42):

A typewriter is an object with keys.

Each of these keys corresponds to one letter in the alphabet.

Chinese possesses no alphabet, but rather entities called “characters.”

There are tends of thousands of characters in Chinese.

A Chinese typewriter must be an enormous device with many thousands of keys.

Steps 1 and 2 form our understanding of what a typewriter is. To ask Chinese to conform to the logics imposed by this understanding, then, required puzzling the language in different ways: common usage supposed that the elemental unit of Chinese writing is the character; combinatorialism, which supposed Chinese characters could be broken up into modular shapes, would then deal with the ramification of its own approach; in surrogacy, characters were not manipulated directly but retrieved via transmission protocols and codes that stood in for the characters themselves (79-80).

While common usage ushered in the era of “distant reading” for Chinese—subjecting language to the brute logic of statistics, determining which parts of the language were more or less important—combinatorialism and its attendant ontology struggled to maintain the delicate compositional balance in characters. It was beset by a politics of aesthetics, as Mullaney puts it (The Chinese Typewriter, 103).

I think surrogacy brought along with it one of the most interesting ideas: long before machine translation, Escayrac de Lauture considered a universal telegraphic language, one to which all languages and scripts would be subordinated, and thus have equal footing. He brought a different approach to a question forced upon telegraphy: would its encounter with new languages, scripts, and so on, prompt a change in the fundamentals of telegraph itself, or would the languages have to kowtow to an existing approach (The Chinese Typewriter, 107-108).

Even more interestingly—to me, at least—de Lauture argued that the physical technology of the telegraph was “an achievement that granted humans a power bordering on the godlike” (The Chinese Typewriter, 108).

The sort of question we just saw—conform, or re-evaluate fundamentals, presented itself again as Remington and its ilk dominated the globe: would those who wanted to invent a Chinese typewriter mimic the technology of the alphabetic world, or chart their own technolinguistic path?

Eventually, a physical implementation of the concept that we struggle so much with—the Chinese typewriter—was developed. You’ve seen a picture of it, above. But it dismisses the logic we use to understand typewriters, to understand basic elements of our interactions with technology. And these logics—pressed into us by the histories of the technologies we use to communicate and write and read—live not just in our minds, but in our bodies.

MingKwai, the typewriter that debuted in 1947, was a successful “failure” in Chinese typewriting. With three negations, Lin Yutang dismissed the three approaches inventors before him had focused on, but managed to integrate them into his machine: common usage, combinatorialism, and surrogacy played a part in the creation of a typewriter that allowed typists to not “type” in the sense that we know, but to command, or instruct the machine to inscribe the characters he or she wanted to type.

When you type Chinese characters on a computer, you are not “typing characters” in the sense that we often think of typing. When you type pinyin, or something else, a menu of characters is presented to you—characters are not “typed” but retrieved.

You are engaging in a different sort of human-computer interaction, with a different interface and different assumptions.

Typing does not have to be typing, apparently. It’s important and useful to deconstruct the categories and assumptions we use to process experience. Objects have politics, concepts are constructions, and so on. But, as Mullaney warns us, deconstruction does not rid us of our assumptions and categories:

To historicize and deconstruct something is merely to destabilize it momentarily, to open up brief and fleeting windows of time in which something—anything—might happen that would be impossible if a given concept were allowed to reside in numb, dumb slumber. But the act of deconstruction does not endure (my emphasis)… In this act we perpetually exert ourselves to drag concepts back mere inches from the precipice toward which everything slides inexorably: the precipice that separates the realm of critical thought from the vast wasteland of the given (The Chinese Typewriter, 31).

To declare ourselves beyond all this, to claim our approaches are truly decentered, then, is to engage in a kind of falsehood. I think—or hope, and really hope—that Mullaney’s words from this introduction, those above and those that follow, will echo in my head for a long time:

I consider this invigorating struggle to be what gives critical thought its primary meaning… Furthermore, I would argue that to eschew or retreat from this agnostic process is to deplete historicism and deconstruction of their only real power. For the scholar who demonstrates the constructedness of a thing, and in any way pretends to have transcended or made unreal the thing thus deconstructed… such acts amount to exiting the field of intellectual struggle altogether, abandoning one’s post, and leaving one’s comrades immersed in a struggle now made increasingly more difficult by being “one intellect down” (The Chinese Typewriter, 31-32).

Critical self-awareness as an isolated act cannot free us, but demands we exert ourselves in continuous struggle.

How Sisyphean.

Does next-token prediction bear any artifacts of false universalisms?

How do you tokenize a character?

Is your thought structured the way words would imply?