patterned integrity (III) — translation and experience

how do you choose a literary translation?

I: there are too many Proust translations

I was deeply suspicious of Pevear and Volokhonsky’s1 Dostoevsky translations when I was younger in large part because they seemed to be everywhere. This isn’t a good reason to dismiss a translation or a set of translations, but ubiquity does make you wonder. Despite my misgivings, I couldn’t escape them entirely. A part of me wanted to care little about translators and worry about the text in front of me; a part of me knew this was impossible, because the translators exerted so much power over my response to a work.

There are more than enough well-informed comparisons between translations, and even criticisms of P&V right here on Substack — I won’t add to them.2 But, because so much of the world’s great literature is only accessible to many of us through translation, it’s worth understanding more about how this all works.

Times that have drawn out national literatures abound: in his Lectures on Russian Literature, novelist Vladimir Nabokov comments on the compactness of the “moment” of Russian literature. While French and English literature have sprawled centuries, the great Russian prose “is all contained in the amphora of one round century” (Lectures on Russian Literature, 32).

Some of that prose needed the real world — that is, Russia at the time that prose was written — to exist. Dostoevsky’s Demons, one of the darkest and perhaps the funniest of his four mature novels, was written to the tune of real political unrest in 1860s Russia. Confused, ridiculous, and violent, it satirizes the clash between younger and older political factions and criticizes the destructive modernist ideology Dostoevsky observed in his Russia. Importantly, Demons offers a window into a part of the world at a particular moment in time. Dostoevsky’s snapshot of “the most important problem of [his] time,” at once political polemic and philosophical foray, is not only fascinating but also important for its criticism of political and social nihilism. In it, we find an argument for the importance of meaning-making structures and a warning against spiritual dangers that trouble us over a century and a half later.3

If these works themselves are important and our only window into a certain experience of the world, then we ought to care about how they’re translated.

And I could have done better in choosing translations. I’ve discovered or chosen editions in a few different ways: I read the Penguin translations of Dante because my high school librarian loved them and suggested I read those;4 I read Oliver Ready’s new translation of Crime and Punishment because my teacher chose it for class; I read Pevear and Volokhonsky’s Demons, The Idiot, and Anna Karenina because they were well-regarded; I read their Dead Souls because it was the only translation available; I didn’t read their War & Peace because I got tired of them and I’d found a pretty hardcover edition in a bookshop.

When I came to Proust, I didn’t do much better — I read the Penguin translations, edited by Christopher Prendergast, because they were new and I really like the way Penguin editions feel and because I’d heard Lydia Davis’s Swann’s Way was a force to be reckoned with, whatever that means. I bought the British editions of the last three volumes because I couldn’t wait for Penguin to release the brand-new US editions with their deckle-edged paper.5

I had only a little knowledge of the depths of discontent about Proust translations when I first read the novel, but anyone who reads even the beginning learns something of the interpretive questions about the volumes’ titles titles. To call the series Remembrance of Things Past as Moncrieff did, or opt for the more accurate In Search of Lost Time? Is the first volume Swann’s Way, which sounds nicer to the ear in English, or The Way By Swann’s, which more clearly indicates that we are walking about a way by Monsieur Swann’s place? Is the last volume Finding Time Again or Time Regained?

Some of these decisions have authority behind them: Proust himself objected to Moncrieff’s Remembrance of Things Past,6 but, as Simon Leser notes in The Drift Magazine, the now-popular In Search of Lost Time downplays the meaning of “temps perdu” as both “lost” and “wasted” time. Indeed, the narrator Marcel experiences and reflects on both of these aspects of his lackadaisical youth. Another option, often exercised by Prendergast,7 is to throw up your hands and refuse to say the novel’s title in English at all, instead enunciating À la recherche du temps perdu every time it comes up.8

Each of these choices is about more than fidelity to the French: a choice is being made about how to interpret and communicate Proust’s intentions with his own titles to an audience who reads English. They impact how we approach and contextualize the work we’re encountering — the image we have of a character, our understanding of their emotions. The novel sometimes presents challenges to forming any theory of mind at all:

To the sight of a pink reflection in a pond, in colorful dialogue with a recently cleared sky, his only response is the exclamation “Zut, zut, zut, zut.” The English language has no direct equivalent for this interjection.’ (Drift Mag)

Indeed, this is an inability to translate one’s inner thoughts into language, any language. That English has no structure mimicking zut, zut, zut, zut isn’t the issue — what needs to be communicated is the impossibility of communicating. I don’t think Davis’ or Moncrieff’s choice of “damn” cuts it, though this is a really funny way to respond to a pond’s dialogue with the sky.

Translators of Proust after Moncrieff find superiority in fixing Moncrieff’s “mistakes,” but the basis for their own work is a moving target: a revised, “corrected” version of Proust’s original manuscript does bring these translators closer to what he actually wrote, but even a manuscript can change and a more accurate rendering of text does not mean a more accurate representation of meaning. Predictably, there is no end to the translators’ disagreements.

So, what to make of the bickering over Proust? At first, Leser’s piece offers little of its own commentary on what makes one translation better or worse — besides statements that bear some judgment on the translators’ opinions of each other — but I think it makes some provocative statements:

[James Grieve, who translated the first and second volumes] attempts instead to re-compose the original in what he posits to be a native English style, hoping that doing so might produce a true expression of the French. But by now the reader shouldn’t expect to be directed toward a flawless translation. Grieve’s is a Proust through broken glass; his feeling for English is simply not on par with Proust’s for French — and that may be what matters most, in the end.

Meanwhile, though Nabokov might have been a great translator for the Recherche because of his own relationship with time and nostalgia — an experience he could channel through his translation — he was too much of a pessimist about the possibility of translation to bring such a thing to life.

Practitioners of the trade generally fall somewhere between two extremes: faced with the impossibility of exact translation, some smile at their condition, finding the gap between two languages to be artistically generative, every new translation revealing hitherto hidden facets of the original work… Nabokov is seated firmly on the opposite end of the spectrum, dwelling in the certainty of failure, mourning the impossible…

On the other side, or at least on that side of the spectrum, sits Lydia Davis. At least some guides to picking Proust translations suggest reading her Swann’s Way, then proceeding with the Modern Library editions translated by Moncrieff, then revised by Kilmartin, then revised again by Enright. The result, which you can find on the top of a little box enclosing the novel’s 4211 pages, is, according to literary critic Richard Howard, “a monument which is also a medium—the medium by which to gain access to the book, the books, even the apocrypha of modern scripture… the surest sled over the ice fields as well as the most sinuous surfboard over the breakers of Proustian prose, an invaluable and inescapable text.”

These are nice words, but I think that in reading translation (as Leser would also agree), it’s also useful to understand the motives and intentions of the translators themselves. Leser gestures in the direction of this point: a translation intended to capture market share might not be our best choice for accessing a text (gasp). Towards developing a theory of mind about translators, I want to draw primarily on two sources: the recent book The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls, a prolific translator who has produced English-language translations of Jon Fosse’s Septology, Wittgenstein’s Tractatus (brave, I know), and dozens of other works; and writing from Lydia Davis, the accomplished translator of Swann’s Way who in her Essays Two offers us discourses on the pleasures of translation and her experience of Proust.

II: translators on translating — Damion Searls and Lyda Davis on the meaning and pleasure of their interpretive art

As Leser observes towards the end of his piece, new Proust translations have billed themselves as not accessible but authentic, truer to the French than their predecessors. This is, I think, where things start to come apart — I don’t know that it makes sense to conceive of “the French” so much as we should be concerned with Proust’s French: how did the author use his language to communicate his experience of the world?

Works of art, Peli Grietzer tells us — including novels and poetry — bear an aesthetic unity or “vibe” that makes up its cognitive content and “model[s] the causal-material structure of the lifeworld.” To gloss much of his point, a work of poetry or a novel — Proust, for our purposes — compresses an experience of the world into its words, offering us readers the ability to witness that totality through grasping this artwork. While composed of words, what we grasp through words has no discursive structure of its own: it cannot be summarized, reconstructed, molded into syllogism.

Moncrieff may have understood this insight better than most Proust translators who came after him, and he lent the Recherche more coherence than one. Leser, in his analysis, concludes that Moncrieff’s translation may indeed have more claim to authenticity than most. For one, it is the only translation of Proust completed entirely by one translator, giving it a continuity that the Penguin and Oxford University Press cycles lack. Second, that Moncrieff’s English was in some ways more old-fashioned than Proust’s French might even work to its benefit: his diction “is wholly consistent with the literary manners of the early-twentieth-century British upper class, whose equivalent in France is, after all, in large part the subject of Proust’s novel.”

If, as Leser writes of today’s environment, the new dueling Proust translations are motivated not by artistic concerns but by sales, we should look on them with suspicion. But how do we decide on the right translation, and what motivations should we look for in translators? Again, in some ways, we’re presented with an impossible epistemic problem: those of us who don’t know French cannot read the original text, so how can we know that our experience of Proust’s world in a particular English translation is anything like the experience of his world in French?

The best we can do, perhaps, is to trust the translators and our own experience. In The Philosophy of Translation, Searls offers his perspective. If the act of reading is a complex interplay between the self and the world, translation is a way of moving through the world.

Searls brings a few ideas together — in particular, insights from the philosophies of perception and language — to develop a theory of how a translator might approach interpreting and translating a text. If I had to give a summary, his fundamental goal is to shift us from the idea that a translator’s job is to operate on a static text in order to bring it to another language with great “accuracy” to the view that a translator “takes up” a source text and, through their translation, offers to readers their experience of engaging with that text.

This experiential aspect is important. When we read, we don’t “receive” a text so much as we engage with it in a two-way relationship: we have our presuppositions, our interests, our inclinations, and the text works on each of us differently because of what we bring to the table. Even when reading works in our native language we find ourselves drawn to different aspects and interpretations of the stories we encounter — we encounter them in our world and our context. Searls draws on Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology of perception in explaining what this two-way interaction means for translation: if the act of seeing develops what’s in the world as we might develop a photograph, a translator takes up the affordances of an original text, “moving through the world and constantly invited to respond in different ways” (125).

Translation adds layers to the activity of the novel or text. Searls argues that a text is not first and foremost an act of communication but simply a use of language that actualizes various potentials in that language. I think we (and Searls) have to be careful here — a text does serve to communicate something, though it also acts in non-communicative ways that act upon us. To act on both these points, it is vital in translating to understand and mimic how a text deviates from or hews to the baseline of its own language.

For example, a German speaker will often say “I want not a salad but a sandwich,” but in English we would instead say “I want a sandwich, not a salad.” Sentence structures and greetings vary, too: Chinese speakers will often greet one another with a contextual question like, “Have you eaten?” Repetition of words is a familiar pattern in some languages, but sounds strange enough to the English ear that we use it for effect. The structures and conventions in one language may feel wholly unfamiliar to speakers of another language. A translation, then, should make use of the resources of its target language in order to deviate from its baseline just as the original text did.

Davis articulates a view on translation that affirms and departs from Searls’. She likes “to reproduce the word order, and the order of ideas, of the original [text] whenever possible” (Essays Two, 4). Searls preaches a looser relationship to these aspects of a text, but her other perspectives mesh well with his: she seeks patterns in an author’s writing and thinks of translation as working in partnership with the author. She quotes Eliot Weinberger to make a point Searls would wholeheartedly endorse:

One is operating strictly on the level of language, attempting to invent similar effects, to capture the essential, without the interference of the all-consuming ego.

Davis understands, as Searls does, that a translator has to use the resources of her own language to produce the effects that the original writer did. But the perspective that most makes me trust her work as a translator is that she sees translation as a way of making a text she loves her own.9 We paint landscapes though we’ll never capture them perfectly, pick up Sibelius although we’ll never play it like Hahn does — in the same way, the translator pursues an imperfection that is entirely and only her own. Davis sometimes even opted to translate with the older edition of Swann’s Way she’d first read to reconnect with her younger self. The sentimental and aesthetic choices made in doing so were entirely her own.

I think, at times, that translators face an impossible task. In laboring over a text, they must intervene on its words and must also get out of its way. Davis’s perspective on how to do this sometimes departs from Searls’ recommendations: in translating Proust she wanted to stay as close as possible to Proust’s original in every way. But, as we read her reflections on what translating closely looks like, we find her paying deep attention to the way in which sentence structure and sound factor into the work’s effect.

Those effects, to Davis, are like puzzles. Her Swann’s Way is in some ways more contemporary than Moncrieff’s (as you might expect of a translation done nearly ninety years later) and tries to recover the original work’s atmosphere. In a scene where Marcel’s Aunt Léonie makes fun of Swann, Moncrieff applies his understanding of the scene’s context — that she is looking over the top of her glasses at him — and offers the word “peep.” But this offers the English reader more context than the French reader, who forms an image of Aunt Léonie without this extra information. Davis opts for the more neutral “look.”

In solving these puzzles, Davis labors over which phrasings best transmit an effect and spends hours researching the etymology of a word just so she might offer to her readers the same experience that touched her. Though she deals with minutiae, I think Davis’s method affirms one of Searls’ most important arguments: translators translate not words but utterances. Working with these larger units of meaning, the translator operates not on the level of a single dictionary entry but the intentions, impressions, and relationships found in text.

While they seem to clash on certain points, I think Searls and Davis have quite a lot in common, and under the surface their preferences point towards a similar goal. Davis might choose to respect formal aspects of a text more than Searls does, but to her, the aim is similar. When she seeks to retain the order of elements in a sentence, the goal is to deliver to the English reader the same process of unfolding that the French reader experiences. They both understand that words on their own do little, but we use words to refer, to create effects and emotions, and imbue them with our intentions — done in the right way, obsession over details recreates these effects in the mind of a reader.

At times, the details are not what we would expect: some translations lay bare that their relationship to the original text has no pretensions to exactness. In Memorial, Alice Oswald offers an “excavation” of the Iliad — she strips the poem of its narrative to emphasize the many needless, heroic deaths that occur in the original.10 An anti-war testament, Memorial focuses its lens on Homer’s (his translators’, really) extensive descriptions of carnage to great effect. One of the more difficult passages for me to get through:

SIMOISIUS born on the banks of the Simois

Son of Anthemion his mother a shepherdess

Still following the sheep when she gave birth

A lithe and promising young man unmarried

Was met by Ajax in the ninth year of the war

And died full tilt running onto his spear

The point passed clean through the nipple

And came out through the shoulderblade

He collapsed instantly an unspeakable sorrow to his parents

Oswald’s verse, a work of its own apart from Homer’s, takes to an extreme many of the principles Davis and Searls discuss. Many of us — certainly Oswald — make our way through the Iliad horrified and sobered by its almost unparalleled depictions of loss. In her rendering, we encounter the Iliad in a form that has fewer words and less of a “story,” but achieves the same emotional effect as the original, if not something even more intense.

III: how to choose a translation?

Choosing a translation to read is difficult. I have some ideas about how to do it, though I wouldn’t call myself an expert. I’ll try to explain some of the ways I form preferences.

“The Man Watching” is, to me, one of poet Rainer Maria Rilke’s most moving works. I think it’s useful to compare translations — I’ll use Edward Snow’s and Robert Bly’s. I don’t know German, so I can’t comment on how their atmospheres compare to that of the original. But I think there are some clear differences in lyricism and vividness between the two.

In many places in The Philosophy of Translation, Searls reminds us that repeated words sound off to the English reader — so much so that we use repetition in form or sound to rhetorical effect. Repetition can be deployed well, but I didn’t like Snow’s in the second stanza:

Then the storm swirls, a rearranger, / swirls through the woods and through time,

Compare this to Bly’s:

The storm, the shifter of shapes, drives on / across the woods and across time

The awkward repetition of “swirls” is just one difference. Bly’s translation focuses the sentence on the storm and its epithet before turning to its action, while Snow breaks up the storm’s action with “a rearranger” — Bly’s storm feels far more imposing. “Shifter of shapes” and “across the woods and across time” feel more musical than “a rearranger” and “through the woods and through time” — the epithet uses repeated sounds, and the choice of “across” rather than “through” lends a cadence that mirrors the fluid motion of a storm rather than Snow’s less sweeping staccato. “Drives on” feels more self-certain and directed than “swirls.” I want this storm to feel powerful, intentional, threatening.

Bly later uses a repetition of his own in the poem’s fourth stanza:

When we win it’s with small things, / and the triumph itself makes us small.

Contrast with Snow’s

What we triumph over is the Small, / and the success itself makes us petty.

The shift in sound from “Small” to “petty” feels somehow harsher, and the sentence’s structure makes the relationship between our victory and smallness less clear than it could be: the first line focuses on what it is we triumph over, then shifts to what this success does to us. In Bly’s, there’s more consistency in the phrasing: “When we win… small things / … makes us small.” There’s a sense of inevitability — the repetition of “small” mirrors the relationship between action and consequence.

At a higher level, though, Bly’s Rilke resonates for me more than Snow’s. Read the two poems in sequence, sound out and internalize them, try to visualize in your head what they’re describing. Months after reading Clive Thompson’s writing on the power of memorizing poetry, I found myself trying to internalize “The Man Watching” and felt Bly’s verse had the vividness I’d imagine Rilke lent to his own images in German.

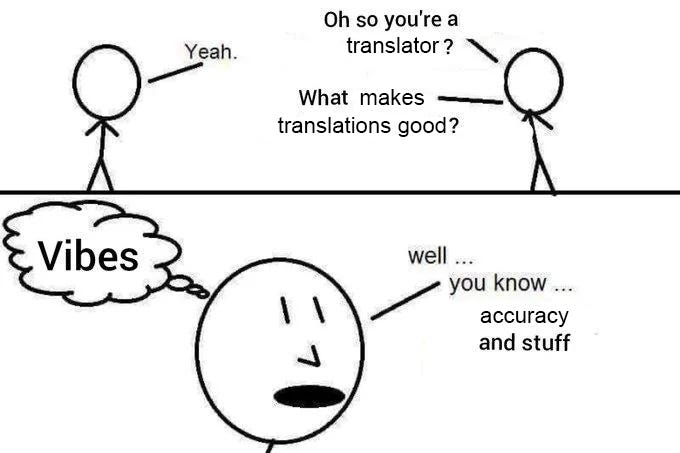

So how do you choose a translation? Maybe you examine translators’ methods and see what makes the most sense to you. Maybe you read their other writing and determine what resonates. But, to beat the point to death, a text offers us an experience of the world, and our decisions about what translations to read are a decision about the kinds of experience we want to open ourselves to. So, we’ve come full-circle: I think you should choose your translations based on vibes.

Also, you should probably read Moncrieff.

often referred to just as “P&V” in the same way Deleuze and Guattari became “D&G” (the cooler / less cool Dolce & Gabbana, I think this comparison really depends on your tastes in philosophy and clothes and perfume but I’ve seen at least one item of D&G clothing that will give me nightmares). also, these abbreviations rhyme (clearly a conspiracy at work here and possibly independent justification for my suspicions, but that’s a topic for a later essay)

to be clear, I think their translations are generally good…

a translation of Demons should, at a macro level, convey Dostoevsky’s gravity and humor; at a micro level, it should communicate historical references, do its best to transpose wordplay, and find ways to mimic other effects

to be clear, this was a great choice

they’ve all been released now, so you can buy them if you want to (this footnote is not sponsored by Penguin Random House)

he did admire Moncrieff’s completed translation, though

we also know that Moncrieff intentionally avoided using the title Sodom & Gomorrah for the fourth volume because he worried about obscenity charges, instead opting for Cities of the Plain (it is really quite a pretty title)

of course, there are times when practicality steps into the mix, and her translation is driven by some combination of making a living and achieving the satisfaction of solving a puzzle.

I loved Davis’ knottiness, the way her English mirrored the flowing entanglement of Proust. It was entrancing to read despite its difficulty, and elevated its subject matter immensely. Less sure about the non-Davis volumes. But I am a strong believer in never reading Victorian language translations of writers who did not write in the 19th century (and in the case of Garnett, who is a smashing bore, even those who did). So no Moncrieff!

Separately I vastly prefer snow to any other Rilke, and from my limited German he most closely approximates the weirdly intangible way that Rilke wrote German a highly tangible language. I suggest you just prefer Bly as an English poet, direct speech and ordinary syntax and all, and that is why you prefer his version. Stephen Mitchell has quite serviceable English versions as well, without the manly pomposity Bly loved.

Finally Pevear and Volokhonsky are totally fine for two reasons: they struggle to place the original writer’s voice into English, weird diction and style and all, and they have made sure that huge swaths of Russian literature comes into translation in their wake (which I acknowledge is not per se a recommendation of their translations but is meant to emphasize their good faith in their approach).

I have read Garnett’s C&P and The idiot and I have read P&V’s versions and the latter is immeasurably better, in narrative drive, in understanding of the original, and in replicating the awkwardness of Dostoevsky which filters every perception of his work.