the third Yes

Leif Weatherby's "Language Machines" and the language no one signs

And shall not Babel be with Lebab? And he war. —James Joyce, Finnegans Wake

Following the digital events of the early 2020s that I need not rehearse here—large language models, to be clear—much of the machine learning community found itself arguing at once about representation geometry and ontology. In plainer words, they were arguing about what distances in embedding space track, and what (if anything) they license us to say about the world. “The Platonic Representation Hypothesis” makes a deliberately speculative leap from a fairly prosaic observation: as models scale, their representation spaces become easier to align. Take two models trained on different data; project their embeddings into a shared space and suddenly “king – man + woman” lands near “queen” in both. Huh et al. take that convergence to suggest a shared statistical model of reality—a kind of modern Platonism in cosine similarity.

Jacob Andreas, a computer scientist at MIT who works on language, offered an apt diagnosis of the instability in the phrase “world model.” In a 2024 essay, he notes that the community slid from asking whether language models can represent “meaning” to asking whether they contain world models at all—and that every attempt to answer this is met with the objection that either “that’s not a model” or “that’s not the world.”

His own proposal is to define several weaker senses in which a predictor can instantiate a world model—map-like, orrery-like (a clockwork model), simulator-like—so that we can ascribe world models to LMs without pretending we have settled the Big Question about whether their computation involves real language understanding. That move—the shift from “does it really understand the world?” to a more fine‑grained typology of what kind of model we’re dealing with—is the kind of reframing I will pursue here, from a different direction.

Humanists, meanwhile, were starting to take note, as language models began to produce writing we had assumed could only be composed by a living person. Ted Underwood, professor of information sciences and English at Illinois, was quick to see what was at stake. In 2023 he described language models as “a triumph for cultural theory” and observed that Ferdinand de Saussure’s distinction between langue and parole is concretely dramatized every time a user prompts a model: the model’s internal system of constraints (langue), on one side, and the particular act of “speech” (parole) on the other. It is as if struct uralism were happening in public, at scale. In a just world, Underwood suggests, every article about GPT-4 would nod toward Barthes and Foucault; that they mostly don’t is part of his joke, and his warning.

If ML people are flirting with Plato again, it’s no surprise that structuralism has slipped back into the room. In his 2025 book Language Machines: Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism, Leif Weatherby takes Underwood’s dramatization as an occasion to rebuild the object “language.” He makes two linked claims about language and LLMs: first, that large language models make it newly urgent to treat language itself—not “intelligence,” not “mind”—as a concrete technical object; and second, that the humanities largely lost the ability to do this when they drifted from structuralism into a poststructuralism obsessed with metaphysical critiques that “floated above the fray.” I want to test the second, because I think the way he stages the Saussure-Derrida disagreement matters for how we read LLMs. I’ll argue, later, that Derrida’s essays on James Joyce complicate the picture of him as simply doing general-economy critique of the “metaphysics of presence,” floating above the restricted economies where we count and analyze words.

To see why this matters, we need Saussure in some detail. Weatherby’s Saussure1 begins by rejecting what he elsewhere calls the “ladder of reference,” which imagines meaning as a climb from word to concept to world, with language as a rung somewhere in the middle—a mini version of Plato’s cave ladder from shadows to Forms. Against this, Saussure insists that language is first “an internally structured web of signs,” and only secondarily a medium for pointing outward.

On Saussure’s account, a linguistic sign is not a label attached to a pre‑existing thing. It is a unit produced by a system that simultaneously cuts across two “vague” continua—thought and sound—shapeless, in his sense, until the system cuts them up together. The signifier is the sound‑image: it is the psychological imprint of that sound, as opposed to the noise in the air. The signified is the concept that goes with it. Crucially, there is nothing inside the word tree that naturally compels it to mean tree—that relation is arbitrary. Yet arbitrariness does not mean absolute freedom. Once a language has stabilized, I cannot simply decree that arbor now means “cat” and expect to be understood. I live in a world with other people who also use arbor. “Tree” also means what it does because it is not “bush,” not “wood,” not “forest,” not “timber.” A sign’s value depends on its place in a system of differences, and that system is continually recalibrated by use. This is the picture LLMs make hard to dismiss: meaning as a position in some general structure, and not a ladder to the world.

For Weatherby, meaning is about value before it’s about depiction. Where NLP’s familiar distributional slogan says that “you shall know a word by the company it keeps,” Weatherby’s Saussure insists on something stricter: value is structured by relations that are simultaneously exchange‑like and comparative. A sign can be “exchanged” for a concept in a local act of signification, but it can only do so because it is also comparable with other signs inside the system. “Meaning,” on this view, is the public calibration of a value system rather than the transfer of private mental content. This is also why meaning cannot be validated by pointing to real trees in the world. The world can occasion use, but it cannot by itself ground the value‑relations that make use intelligible as language.

Underwood’s point that prompting “concretely dramatizes” parole and langue thus becomes, in Weatherby’s hands, an invitation to treat LLM output not as a miracle of reference but as a visible instance of valuation‑under‑constraint. The prompt is a parole‑event: a particular speech-act addressed to the system. The model’s weights encode something like a langue: a learned space of acceptable next moves that defines, in a statistical way, what counts as a “word” or a “sentence” here. Ask a model to continue “Once upon a…” and you’re already leveraging that space of acceptable continuations.

Because Saussure already gives you a material signifier (the sound‑image, not the thing), systemic value, and no language-external measure of meaning, many of Derrida’s most famous “anti-structuralist” formulations—“every concept is inscribed in a chain or in a system”—can be read, Weatherby says, as intensifications of Saussurean relational value rather than departures from it. The flashpoint comes over one sentence. Saussure notes, almost in passing, that “historically, the fact of speech always comes first.” Derrida seizes on that aside in Of Grammatology to diagnose a hoary philosophical preference—what he calls “phonocentrism.” Voice feels like meaning in the act, present and immediate; writing gets treated as a belated record. Once you grant that hierarchy, “origin” starts to sound like voice, and everything else looks like supplement or detour. Derrida uses that remark to motivate a shift from semiology to the metaphysics of origin—recoding semiological dynamics in the vocabulary of “production” and “constitution” and then declaring that very vocabulary complicit with metaphysics.

Weatherby balks at Derrida’s jump here, and there is good reason to balk. If what Saussure meant by “parole comes first” was simply that values shift and stabilize only in use—a descriptive claim about how sign-values calibrate in practice—then turning that claim into evidence of an ontological “causal act” that brings language into being looks like a category mistake. Crucially, though, the impulse to convert restricted bookkeeping into a story about origin and presence is not simply Derrida’s personal whim; it is baked into the conceptual repertoire that mid-century theory inherited. Bataille’s contrast between a restricted economy and a general economy is helpful for naming it. A restricted economy is the bookkeeping of a closed system: what comes in, what goes out, and how value is conserved. A general economy widens the frame to what exceeds any ledger—expenditure without return, surplus, waste, circulation. Derrida’s appeal to Bataille’s distinction between restricted and general economy—developed most fully in his essay “From Restricted to General Economy” in Writing and Difference—is part of his broader attraction to surplus and excess. Weatherby’s charge is that reading Saussure’s “priority” remark as metaphysical slides us, too quickly, from a restricted economy of sign-values into a general‑economy story about “origin” and “presence” circulating in metaphysical discourse.

Weatherby will even grant Derrida a crucial point: there is no final “general equivalent” in language. A “general equivalent”—a gold standard of meaning that could cash out every other sign without itself being a sign—does not exist. If it did, we would have a metalanguage. But he refuses to follow Derrida all the way into poststructuralism, because in his view poststructuralism’s drive to rephrase structuralism’s “concrete object” in a higher key (“writing,” “trace,” “Différance”) in the name of anti‑metaphysics ends up, as he puts it, “floating above the fray”—precisely where today’s object now sits, at the interface of numbers and words in restricted technical systems.

The cost, in Weatherby’s telling, was methodological. In training themselves to hear “writing,” “trace,” or “signifier” as names for a general condition (a metaphysical critique) rather than as handles for analyzing specific sign systems and their interfaces, especially those with mathematics and computation, humanities scholars lost the analytic habits that structuralism specialized in: tracking structure, regularity, distribution, and a system’s differential constraints as a concrete object of inquiry.

Weatherby is at his strongest when he brings this back down to tokens. The token is indeed a common currency between language and computation. In LLM work, a “token” is the chunk of text the model operates on—those subword pieces GPT chews through. In an older semiotic sense, a token is one concrete instance of a type, like this occurrence of “tree” on your screen as opposed to the abstract word. Tokens in this doubled sense are both the discrete units a model ingests and the fungible instances of a type that circulate in a system, exchangeable under constraints. That double status is why they demand restricted‑economy analysis.

If we go back to Derrida with that in mind, things get interesting in a different way. The Joyce essays do not look like “floating above the fray.” They are, in fact, obsessed with units: what counts as a word, a repetition, a “yes.” In “Two Words for Joyce,” Derrida begins with an almost pedantic promise—two words—and then turns that promise into a problem: supposing words in Finnegans Wake can be counted at all, what is it we would be counting? Joyce scrambles not only meaning, but the unit of account. Derrida’s minute attention to spacing, letter, and count there looks, in Weatherby’s terms, like restricted economy at work.

The two‑word object Derrida chooses, “HE WAR,” is a small device that forces interfaces. Read it as English and it leans toward a verb phrase (“he wars”); read it as German and it leans toward tense (“he war” / er war, he was); hover near it and wahr (true) emerges. Commentators have counted still more languages lodged in the phrase. Spacing becomes a mechanism; so do typography and translation. Derrida is not invoking “free play” in the abstract, but showing how a concrete sequence forces decisions about whether you are reading with the ear or the eye, which language boundary you are drawing, and what you think the signifier is after all. The question “how many languages in two words?” is also the question “how many tokens, and which ones?”

Then he scales the device up. Joyce becomes a “hypermnesiac machine,” a thousandth‑generation computer whose capacity to integrate variables makes contemporary computers, micro‑archives, and translation machines look like child’s toys. Here Derrida is already naming something like the language‑machine interpenetration Weatherby claims the humanities refused to theorize. But Derrida deploys the machine‑image to press a limit. You can’t “integrate all the variables” without a machine capable of integrating all the variables. Absent that, the dream of full accounting remains structurally compromised. Whatever machinic Joyce is, it is not the same as our machines.

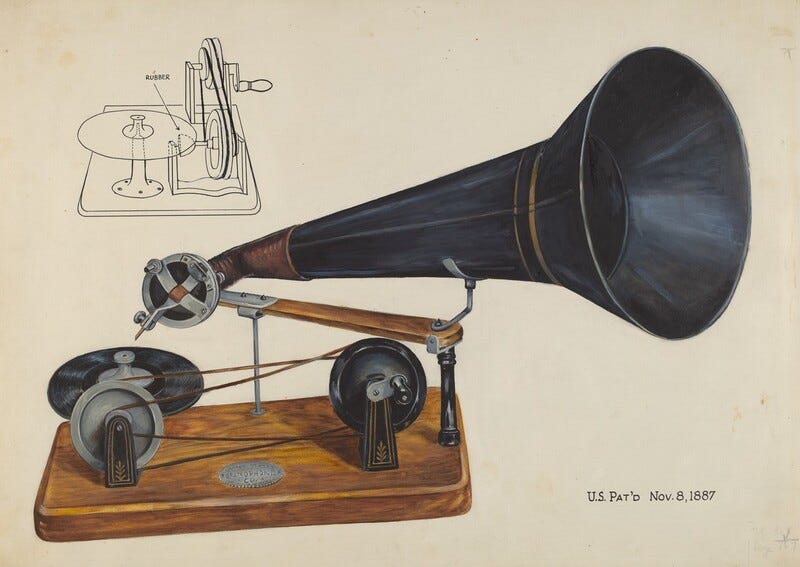

“Ulysses Gramophone” makes the stakes even clearer. As critics like Paul Saint‑Amour reconstruct it, Derrida splits the figure of the computer in two. On one side stands the present-day machine of preset operations: the completist archive, the competence fetish that would reduce Joyce to exhaustive routines and recordings, the gramophone that can replay “yes” forever. On the other side stands an “as yet unheard‑of computer,” able to respond by integrating with the work and adding “its own score, its other language and its other writing.”

What Derrida stages here is not a human-versus-machine standoff so much as a contrast between processing and countersigning. Very roughly: processing is what a system can do with a mark; countersigning is what a subject does when they let a mark speak for them. To countersign is to sign next to someone else’s signature—to add your mark to an utterance and be bound by it. For Derrida, this is the kind of response that assumes responsibility, rather than just replaying or recombining what’s already there.

The language machines we now have land somewhere between Derrida’s two computers. This is the kind of fine-grained distinction Andreas was calling for—not “does it understand?” but “what kind of model is this?”—though arrived at from the other side, through Derrida rather than cognitive science.

On one hand, they are unmistakably the first machine: systems trained to maximize predictive fit, producing language via learned operations over distributions. On the other, they do add writing. They don’t merely retrieve or index. They generate new text, and sometimes that text has the surface texture of response. But the “response” is not answerable, in Derrida’s sense, to singularity. It isn’t a countersignature. The model has ingested its training material—tokens among tokens—and its continuations are calibrated to statistical regularities, not to the responsibility Derrida associates with a reply “unique and unforeseeable.”

That mismatch highlights the contemporary strangeness. Derrida couples generation to answerability: the unheard‑of computer produces because it responds, because it enters the scene as a countersigning agent. What we have is generation decoupled from that structure of responsibility: production that can mimic address without being grounded in a responding subject. “Writing without reading” is a little too blunt, but it is close: writing that follows from ingestion and optimization rather than from the hermeneutic scene Derrida treats as constitutive of response.

This is where Weatherby’s call for restricted-economy analysis bites. Whatever else these models are, they are determinable systems: units, constraints, regularities, distributions, interfaces where number and word meet. If poststructuralism trained the humanities to treat “writing,” “trace,” and “signifier” primarily as names for a general condition, LLMs force a descent back into the object—how tokenization discretizes, how attention allocates weight, how training dynamics turn co‑occurrence into structure, how “value” emerges as position in a high-dimensional relational field.

But the Saussurean return is not a final resting place. The analogy is real: significance as position in a system rather than a ladder from word to world. Yet Saussure’s langue is a social fact calibrated through use; a model’s “knowledge” is a statistical artifact tuned by gradient descent and later normed by human interventions. Weatherby is right that this is where number and word meet—and right that we lost habits of analysis that could have met it there.

He is not, I think, right that Derrida only floats above this fray. In the Joyce essays, at least, Derrida is down in the machinery: counting units, worrying about what can and cannot be computed, distinguishing between a gramophone’s mechanical “yes” and a countersignature that binds a subject. That distinction matters now. Underwood’s “empirical triumph of theory” says that models like these vindicate a structural theory of language: they literalize Saussure’s web of differences at scale. But they do not vindicate the idea that language is nothing but that web. The unheard-of computer, if it ever arrives, would need to both manipulate tokens and answer for them. We are not there.

If the Platonic Representation Hypothesis tempts us to imagine our models climbing out of the cave and discovering the real, Saussure and Derrida suggest another picture. The models’ internal geometries do converge, but what they converge on is not the world itself; it is a value-system that happens, contingently, to be useful in navigating it. This is the restricted economy made legible.

We can, for once, actually see the ledger Weatherby wants us to keep: tokens, distributions, attention weights, the geometry of a representation space. If you cannot take apart a tokenizer, you will miss the object, and on that point he is right. But the column for “signature” is blank. No amount of gradient cunning backpropagates a subject position. A model can learn the cadence of signed prose without acquiring the capacity to sign.

That gap is not a deficiency we will patch with more training. We have engineered a separation between making a mark and being bound by it. Joyce gives Derrida a gramophone that can replay “yes” forever and an unheard-of computer that would reply with a “yes” someone would have to stand behind. Our language models generate a third “yes”: fluent, generative, unsigned. It is not replay—nothing is merely retrieved. It is not countersignature—no one risks themselves. It is language that arrives with the grammar of address and no addressor.

Readers have always had to turn ink into act, but countersigning is more than “making meaning.” To countersign is to let a sentence obligate you, to put your name next to it and be on the hook for what it does in the world. With machine text that exposure does not happen at generation. If it happens, it happens downstream—when someone forwards the line, files it, publishes it, allows it to stand as their own. These yeses go out into the cave unsigned. If they bind, they bind later, in a million small acts no loss function tallies.

The diffusion of that binding is the political form hybrid writing takes. Attribution protocols and crafty watermarking won’t supply a missing general equivalent here. We will have to decide, in courts and code and style guides, who gets to let a machine’s “yes” count as an answer. We almost certainly won’t invoke Saussure when we do. The yeses arrive unsigned. Those who speak them do not.

slight correction / note that I neglected to make when first writing this: Weatherby’s Saussure was first Pourciau’s Saussure. see also The Writing of Spirit: Soul, System, and the Roots of Language Science.

such an amazing review -- and i actually agree with you mostly about Derrida, his stuff on writing and machines is about as good as theory gets about writing and machines (so far). i don't think he's lacking responsibility for the abandonment of the restricted economy that the next generation undertook -- and i'm not sure i'd go as far as to hold up Ulysses Gramophone as an example of the countertrend, i want a fictional JD who connected the general and restricted economies by way of ideology, cultural laws, disciplines -- but it's not so important. very grateful for this, and would just add that "Weatherby's Saussure" was Pourciau's Saussure first

I've been grappling with these questions for a while--aided also by Weatherby's incredible book--and this review is great food for thought. In particular, I appreciate the point about countersigning: "To countersign is to let a sentence obligate you, to put your name next to it and be on the hook for what it does in the world." I think the question of who takes responsibility for AI writing will be increasingly important. In teaching, I've built my AI policy around accountability, following the journal Nature's policy from Jan 2023. Regardless of origin, our words will need to be signed.