A pattern has an integrity independent of the medium by virtue of which you have received the information that it exists. Each of the chemical elements is a pattern integrity. Each individual is a pattern integrity. The pattern integrity of the human individual is evolutionary and not static.

—Buckminster Fuller

The word “meaning” somehow frustrates itself in self-application. It fails to capture what it tries to mean. To rephrase in a more confusing way: it’s hard for us to get a grip on what “meaning” means.

Or, at least, I have a hard time getting a grip on it: how to think about what anything “means” and how to think about meaning. In the same way that Hume problematized our knowledge of cause and effect because the world only presents to us patterns of repeated occurrences, so too does Hugh Kenner question what we can know of any sort of truth or meaning through language: “[Homer’s] poem is not its language. It exists, just here and now, in this language, this niceness of linguistic embodiment, inspection of which will tell us all we will ever know about it” (The Pound Era, 149).

Some have proposed that there exists some higher, purer realm that stands closer to truth than our language. In Analytic Universal Telegraphy, Escayrac de Lauture1 wrote that the telegraph “must have its own language, which places itself between our vulgar idioms and that higher form of language which our mind can conceive.” We might think of language as it existed before the Confusion of Tongues: a state of affairs where you and your almost-friend from across the world, who today might be totally unintelligible to one another, could pass the time completing the system of German Idealism together.

A world where we don’t need Google Translate. A more boring world in many ways. A world where David Pfau doesn’t feature this photo on his Twitter profile2

And yet, you and I, speaking in the very same language, hardly understand one another. You can’t be totally certain I’m conscious — so how the hell do you know what I mean when I say something?3 There is a reason we have to cajole ourselves to “say what we mean”: we are hardly capable of translating that elusive quality into words, even when it exists in our own heads.

Nonetheless, we attempt to get close to what we mean in language: the best kind of writing, to me, strives for a pure image, conveying the world as closely as it can. This does not always mean simple language and straightforward descriptions: when you refer to “a book on a table,” there’s always more than just a book and just a table. I don’t use “describing,” because I don’t think the most faithful and forceful communications of reality attempt to describe or refer to it.

“Pure image” calls to mind Imagism — poetry does demonstrate this deeper ability to convey. Peli Grietzer, in one of my favorite essays, expands upon the concept of the empirical to offer a theory of the interpretation of poetry: “Poetry, as the imaginative grasping of a world’s coherence, is in part ‘about’ the same thing as the scientific image: the causal-material patterns that make rational life possible.” Peli uses an analogy to the autoencoder to specify just what’s going on with poetry and the meaning it makes possible — the clues machine learning provides allow us to ground a story about art’s significance in the scientific image.

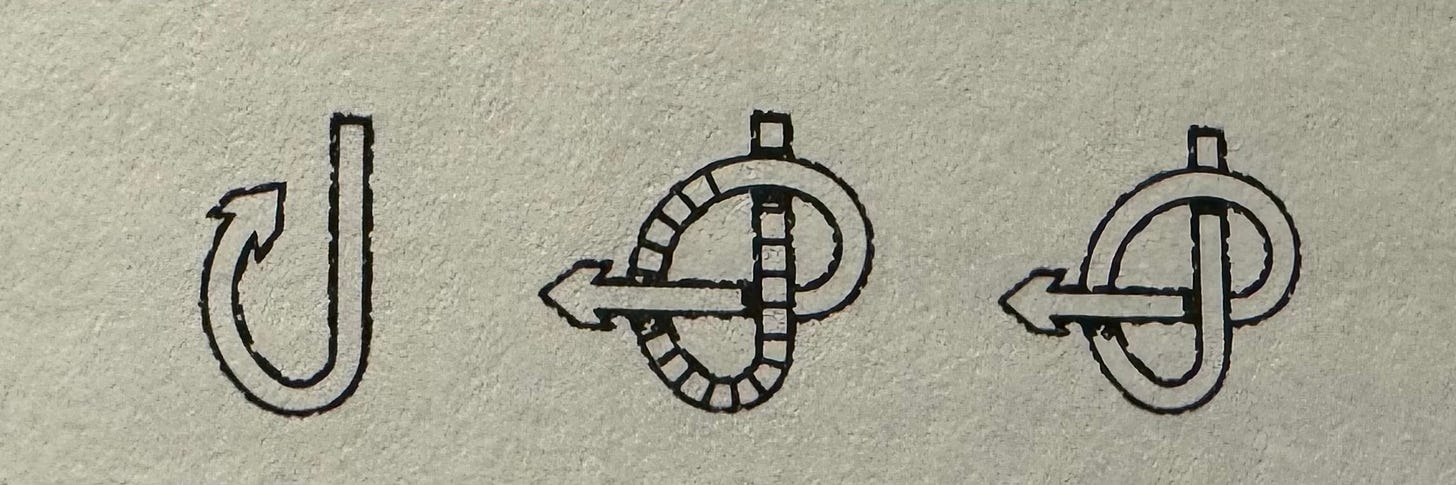

Going further, Peli argues that it is specifically the non-referential nature of poetry that renders it capable of holding meaning, without our directing it to do so. Peli tells me he hasn’t read Kenner’s Pound Era yet, but his own language recalls Kenner4: “It’s a knot of thoughts and feelings and perceptions that amounts to meaning through material force, so to speak, rather than through our protocols of sense-making.”

To grasp a poetic thought, then, involves a non-discursive leap. The poetic thought, through a force its writer could not endow it with, perfectly conveys something of the world. As a result, summarization is doomed to fail. It is perhaps the realization of this non-discursive force in poetry that appeared when Ezra Pound wrote to Michael Reck about the translation of a Japanese Trachiniae from his own derived translation: “Don’t bother about the WORDS, translate the MEANING.”5

This patterned force appears in more than just poetry — consider the novel. Just as Pound’s Canto I exhibits Homer as a persistent pattern (The Pound Era, 149), so does The Recognitions owe great debt to Joyce. Even in form: em dashes announce dialogue instead of the perverted commas Joyce despised. But it’s unclear just in what way Gaddis related to Joyce, since he contests or at least questions the influence:

I recall a most ingenious piece in a Wisconsin quarterly some years ago in which The Recognitions’ debt to Ulysses was established in such minute detail I was doubtful of my own firm recollection of never having read Ulysses. (letter to Jean Howes, March 1972)

The parallels feel clear for us readers, if we stop to look: in the opening paragraph to Ulysses, “stately, plump Buck Mulligan” acts out a mockery of a Catholic priest performing Mass; the first chapter of The Recognitions more explicitly references Catholicism6. It contains one of the most provocative images I’ve ever read:

“The father and son faced one another across the stark declivity of their different heights, the man staring wordless at this incarnation of something he had imagined long before, in a different life; the child staring beyond at his virgin mother” (The Recognitions (NYRB edition), 25).

If you’re looking for utter force in language, look for images like this one.

Kenner draws out the notion of patterned integrity into what begins to feel like a theory of everything. Retelling the story of scientific advances in the 20th Century, he observes patterned energies in Einstein’s finding that mass is energy, in the entire universe. We should remind ourselves that Kenner is talking of Imagism, which seeks precision of imagery. But he clearly wants to speak about more, and his ideas have compelling extensions: nature indeed appears to have no grammar.

Kenner doesn’t make the bounds or details of his theory — or its status as a theory — wholly clear, but his ideas bear traces of the observation that we project the features of language onto a world that doesn’t bear them. Appropriately, or annoyingly, he elucidates patterned integrity not through direct reference or a definition but through anecdotes, examples from the Cantos, notes from Pound, notes from Ernest Fenollosa.

If there’s anything to come away from Kenner’s prose with, I think it’s something you’ve heard before, communicated to you by the force of his words: the human condition, to recall Buckminster Fuller, is a sort of patterned integrity; it’s arrogant to think you can legislate meaning through your words. Not all speech or language use is poetic, but much of it bears poetry’s quality of eluding our control.

Peli’s work seeks to explicate the mechanism by which poetic language transmits something that appears to us as meaning. This language — found in not just poems but novels, paintings, music, and films — manages to stir something in us that we experience as meaning, but that isn’t ours to define. Insofar as art offers us a deeper sort of experience than other forms of expression, then, it makes clear to us that the attempt to find meaning by analysis is a doomed project.7

In another very important sense, though, I think we can say that poetic language is ours to define. Sally Rooney’s T.S. Eliot lecture meditates on the multitude of mutually exclusive readings in Ulysses — is Leopold Bloom looking for a son and Stephen Daedalus looking for a father? Joyce’s writing certainly admits this reading, even if it doesn’t fully endorse it — and concludes that its flouting of convention and destabilization of language all serve the purpose of allowing us, the readers, to more fully appreciate its beauty.

Rooney, as she explains, reads Ulysses with the background of being a novelist and being a woman: these ultimately determine the work she reads. She didn’t choose her sex, but being “a person who studies novels, reads them for pleasure, and even tries to write them” is very much a choice about what to do with one’s life. In this sense, she defines her Ulysses by being who she is and responding to the person she is.

I don’t know where all this leaves us, but maybe we can say a few things. Insofar as we are unknown to ourselves, we can’t know why art works on us the way it does. When we attempt to describe art to others, to become critics, we often say less about the art than we do about ourselves. The attempt to mutate art into language can be a vehicle of self-recognition.

This clarifies for me, a bit, why I always fail to find words for some of my favorite novels and why I have to tell people to just read them, because there’s so little justice I can do. But perhaps the attempt to do justice is just another way of making myself known.

maybe it’s not that utopian

hell, I’m sometimes at pains to figure out what I mean when I say something

or maybe I’m just reading too much into the word “knot”

classic theories of meaning consider how symbols refer or “hook onto” things in the world — Frege famously addressed differences in the cognitive significance of expressions (e.g. that “Superman” and “Clark Kent” refer to the same person, but you might not know that Clark Kent is Superman) by distinguishing sense (“mode of presentation”) from reference. Russell, a pivotal figure in the linguistic turn, held that the only directly referential expressions are logically proper names.

if you’ve finished reading this footnote: none of this is actually relevant to what Pound is saying, but it is fun trivia for your next date

not just the introduction, since Christianity is laced throughout the book. At least one paper calls it “the last Christian novel.”

I think Susan Sontag would happily endorse this sort of normative takeaway from Peli’s work

Hmm this makes me question a lot about the unreliable narrator as a vehicle that takes you further from the actual meaning of a piece. Especially in speaking of art or describing things, as you mentioned, it's a disservice to 'explain' things, in essence. We end up playing a long drawn out version of telephone when retelling the tales of a produced piece. But that also becomes an art in and of itself - one that evolves over time and picks up seasoned flavors of multiple storytellers and writers and 'describers'. Different people will make sense of the same reality in diverse ways, therefore multiplying our shared experience.

I could spiral here if not careful. You've given me much to think about, thank you.

You might like this old 2009 post of mine https://www.ribbonfarm.com/2009/03/26/the-tragedy-of-wiios-law/

I think of meaning as a kind of intersubjective aha, what in the post above I refer to as a game-break, when 2 minds make sense of a new bit of unfactored reality in the same way. There is not just recognition of the thing, but mutual recognition of mutual recognition of the thing, creating a bond between two minds and a separation from other minds that have not shared that experience. Illusory one-way versions of this present as stalking and obsession. An individual alone cannot create meaning as such. Only wordless, meaningless horror of a labatutian “when we cease to understand the world” variety. A lot of the skill in skilled interviewing, which I think you do intuitively, is engineering game-breaking meaningful moments live, on record. Conversations that lack that sound dead in a way.